By Lance Wakely

Peter’s career in Greenwich Village and on the road with the Phoenix Singers had more downs than ups—and so he went west, to Hollywood. The rest, as the phrase goes, is history. Peter as he appears today on The Monkees.

In January 1964, Peter Tork took a brief respite from his “impoverished” existence in Greenwich Village and went off to Venezuela for a month with his parents, John and Virginia Thorkelson, his younger brothers, Nick and Chris, and his little sister, Ann Elizabeth. When Peter came back, he showed me lovely, glowing color photos of himself and the family (who I hope you all get to know better one day, for they are as interesting as individuals as Peter is). There were shots of Peter and Nick by fountains, the family in front of the hotel and—you know, souvenir photos like that. It was kind of funny, because right in the middle of showing them to me Peter stopped and said, “You know what? It was fun, but I missed the Village. I mean, man, I really wanted to be back here.”

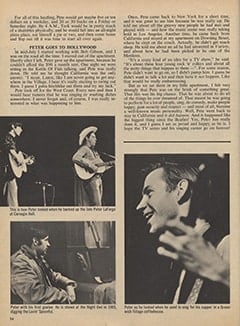

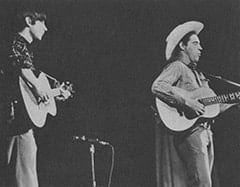

Well, back he was—and we were both at the old routine of trying to find work in the Village. Then, one night something happened that was nothing short of a miracle. Peter came flying into the Four Winds, a coffeehouse on Third Street, in a high state of excitement, shouting, “Guess what, you guys!” And he told us about his impending debut at Carnegie Hall. He told us that he had been hired to back up singer-composer Peter LaFarge (who later died in an unfortunate accident). Peter LaFarge was one of the acts invited to appear at the first New York City folk festival (and, I might add, the last) at Carnegie Hall. The festival starred such luminaries as Johnny Cash, Phil Ochs, the late Mississippi John Hurt, and a full range of folk personalities spanning the entire history of the idiom. Though the folk festival was not the financial success we had hoped it would be, it was certainly an artistic success—and it was a real kick to see Pete right up there on stage with the best of them. Tork and I continued goofing around together. In fact, we were together quite a bit. We rehearsed together, played together and chased a lot of girls together.

It seems that we always went for the same girl, and I guess that is when our “trouble” began. Suddenly, we were in constant conflict. We had differences about girls, and then we had differences about our work. What we didn’t realize at the time was that this was a normal competitive “thing”. We were constantly employed by the same people and quite naturally we tried to outdo each other in order to please our employers.

It was at about this time that we both got into the Phoenix Singers. We worked with the Phoenix Singers for about seven months, and during the last couple of months there were bad vibrations in the air. Pete loved to clown around on stage and the Phoenix Singers didn’t dig that. Pete also disliked being ordered around or told what to do. These two elements clashed, and the fireworks that resulted were the following:

It was in October 1964, and we had just finished an in-person, fund-raising concert for Lyndon B. Johnson in Denver. As I said, the pressure had been building for several months. Two of the Phoenix Singers didn’t want Pete in the group, but my buddy Ned wanted him to stay because he dug him musically. I had mixed feelings at the time. I agreed that musically Pete was excellent, but I felt that he had to cool it a bit on stage because there was a personality conflict between him and the two Phoenix Singers mentioned. Anyway, after the LBJ thing in Denver we were preparing to drive back to the hotel in a rented car and Peter, who was going to drive, said, “Everybody put on your safety belt.”

Ned, who was in a bad mood, said, “No.” Peter told him once more to put on his safety belt, and once more Ned declined. Soon, they were at it. Ned got loud; Pete’s face got red; and I retreated into a corner of the car.

Flash! Out came Pete’s stubborn streak: He said, “O.K.—if you don’t put on your safety belt, I refuse to drive.” And he folded his arms and sat rigidly in the driver’s seat. In a fit of temper, Ned got out of the car and told Pete, “Get out!” Pete removed his safety belt and angrily got into the back seat of the car, and we drove off.

At the airport, we got on the plane to New York. It was on the way from Colorado to New York, at 30,000 feet in the air, that the three Phoenix Singers had a meeting, and two against one (for Ned still dug Pete’s musicianship) they voted Tork out of the group. Peter was quiet for the whole flight, and I could tell he was not very happy. I don’t think he cared about the Phoenix Singers that much, but I think he cared about the security that the job had provided and the fun he had been having on the road.

I stayed on with the Phoenix Singers for quite a while, and Pete went on to the old routine down in the Village. During this time he spent most of his weekends at his parents’ home in Connecticut. Sometimes I would stay at his house, and we would go out and sing in the coffeehouses together. In March 1965, I moved in with Pete for two weeks while I was looking for an apartment. The girls upstairs (whose shower we used to borrow) moved out, and Pete and I decided to take their apartment.

A typical day with Pete Permalink

Info Peter with his first goatee. He is shown at the Night Owl in 1965, digging the Lovin’ Spoonful.

Info Peter as he looked when he used to sing for his supper in a Greenwich Village coffeehouse.

Peter Tork didn’t have much of a “good time” life in those days. He really had to hustle to make a living—in fact, we all did. Here is a typical day in the life of Pete in the Village in early 1965:

He would get up in the afternoon, and if he was lucky he would have something around to eat. If not, he would go down to MacDougal Street, hoping to run into a couple of chicks who would give him some lunch—and, usually he did and usually they did. About 3 in the afternoon he would come home, and we would rehearse and work on new numbers ’til 8 at night. Then Pete would take off on the coffeehouse routine. It seemed that the tourists got stingier with every passing day, so ultimately Pete had to do what we called doubling. That meant working two houses or more in the same night. Like he would play 20 minutes in the Night Owl, and then he would run to the Gaslight and play 20 minutes there, and then he would dash to the Basement for a 20 minute stint, and then fly over to the Pad for a 20 minute turn. Man, just the running around was exhausting, but when you consider all the playing and singing he did—well, Peter Tork sure is made of iron!

For all of this hustling, Pete would get maybe five or ten dollars on a weekday, and 20 or 30 bucks on a Friday or Saturday night. By 4 A.M., Tork would be in pretty much of a shambles physically, and he would fall into an all-night pizza place, eat himself a pie or two, and then come home and flop out till it was time to start all over again.

Peter goes to Hollywood Permalink

In mid-July I started working with Bob Gibson, and I was on the road all the time. I moved out of the apartment. Shortly after I left, Peter gave up the apartment, because he couldn’t afford the $90 a month rent. One night we were sitting in the Kettle Of Fish talking, and Pete was really down. He told me he thought California was the only answer. “I mean, Lance, like I am never going to get any where in the Village. I hear it’s really starting to swing out there. I guess I gotta hitchhike out there and try my luck.”

Pete took off for the West Coast. Every now and then I would hear rumors that he was singing or washing dishes somewhere. I never forgot and, of course, I was really interested in what was happening to him.

Once, Pete came back to New York for a short time, and it was great to see him because he was really up. He told me about all the groovy new people he had met and played with—and how the music scene was really taking hold in Los Angeles. Another time, he came back from California and stayed at my apartment on Downing Street, where he slept on the couch. Actually, he didn’t get much sleep. He told me about an ad he had answered in Variety, and about how he had been picked to be one of the Monkees.

“It’s a crazy kind of an idea for a TV show,” he said. “It’s about these four young rock ’n’ rollers and about all the nutty things that happen to them—”. For some reason, Pete didn’t want to go on, so I didn’t pump him. I guess he didn’t want to talk a lot and then have it not happen. Like that would be really embarrassing.

But as we sat there in my little apartment, I felt very strongly that Pete was on the brink of something great. That this was his big chance. That he was about to do all of the things he ever dreamed of. That meant he was going to perform for a lot of people, sing, do comedy, make people happy, gain security and respect—and most of all, become a well-known music personality. Well, Pete went back to stay in California and it did happen. And it happened like the biggest thing since the Beatles! Yes, Peter has really done it, and I guess I am as proud and happy, as he is. I hope the TV series and his singing career go on forever!