On December 30, 1946 (Actually 1945) David Thomas Jones began life in a poor, down-trodden section of Manchester, in England. The only celebration was by the joyous parents who already had three daughters, and wanted desperately that this last child be a son.

As Davy grew, his childhood was similar to all his “mates,” with some striking exceptions. His parents, poor as they were, tried to lend some dignity to their drab lives. While no other families would go on vacation, Mr. Jones would save his money towards an annual two-week holiday at a beach called St. Anne’s. And while the other parents would be going out in the evening to pubs, spending their extra money on drinks, the Jones stayed home. Consequently everything was paid for on the spot, and the horrible curse of debt never touched the Joneses.

Then tragedy struck. Davy’s mother, who had worked so hard to keep their home warm and genuinely happy, passed away. Davy took a long thoughtful look around him… at the poverty, at the unhappiness of his friends; his father wasn’t well, and his sisters would be marrying soon and leaving home.

It was time for Davy to leave and seek his fortune. And so he decided to do what nobody he knew had ever done—he was going to make his own, personal fortune.

He was just 14 ½ when he left home to do just that.

Davy’s story Permalink

Davy looked about him. He had a less than average education, and had hated studying in school. “I started acting a lot in school to get out of the lessons,” says Davy. “I’d say I can’t do this because I’ve got to learn my script for the part. Of course it was still eight months before the show went on. I was really a con man in school.”

But in one subject Davy was fantastic—acting. His friends, teachers, everybody who’d ever seen him told him he should be an actor. He even had a fling at one professional radio show in Manchester. But Davy wanted money, and immediately. “So I decided to leave home and become a jockey and make some money fast.”

Whether you call it fate or plain luck, stable boy/jockey Davy couldn’t get away from show business. Being zany and attracting attention was in his blood. He could do anything without suffering any self-consciousness. And it’s very typical that his first break happened while he was caddying on a golf course!

Davy is discovered Permalink

“While I was in the stables a producer who owned horses used to come and play golf with the trainer. I used to caddy for them—and I’d sing. They said I ought to be in show business, and the producer liked me enough to recommend me to other people in London.

“So suddenly I found myself taking trains into London on the weekends because I was asked by various people to do radio and TV shows.”

Davy was a fantastically hard worker but he had to stop somewhere. Every day he’d brush his horses, “muck” (clean) out the stalls and ride. After the rest of the boys were in bed he’d go over what he had to do that weekend. Friday would come. Chores all finished, Davy would run to catch the local train to London and his weekend acting career.

“Finally the trainer told me I had to decide which I wanted to do. While I was going away on the weekend there was more work for the other lads who were left in the stable. They’d have to clean out my stalls and feed my horses and it wasn’t fair. He simply said, ‘You have to decide what you want to be, an actor or a jockey.’ Then, because he was like a father to me, he said, “You ought to go out and make money so you can own your own horses.’

“That made my mind up. I went to London to audition for some agents who used to come down and play golf.”

A new career Permalink

The agents really dug the cocky 15-year-old who handled himself like the best of professionals. After they saw his routines they liked him so well they did an unheard of thing. They sent this unknown—a country boy just one day in the city—to two of the most important auditions in the city. Both were on the same day.

So Davy set out for his first audition. He felt no fear, just curiosity and a desire to show the “bigwigs” he could compete with the best of them. His first audition was for the part of the Artful Dodger in Oliver. “I walked in and suddenly I did feel a little scared. But I had the idea then and still do, when you have a part, or whatever you’re doing, put yourself in the position that you are the person you’re playing. So I just put myself in it and forgot to be afraid.”

Davy sang a song and the producers were obviously impressed. But then they asked him to read some lines. Davy opened his mouth and out came his thick North Country accent. Since the Artful Dodger had to have a Cockney accent they said they couldn’t use him. Then, as an afterthought—or a joke—they told him to come back in six weeks with a Cockney accent and he’d have the part.

Davy walked out the front door of the theatre, down a few blocks and into the audition for “Peter Pan.” “They signed me up on the spot,” says Davy, “and the next day the whole company went on the road, and I didn’t know a line of the show. I learned my lines on the bus on the way to Glasgow, where we opened.”

A will to succeed Permalink

People knew upon meeting Davy that he was bright and clever, but nobody realized the fantastic will that was buried under that innocent-looking surface. Davy rehearsed for Peter Pan during the day, did the show at night, and spent the rest of his spare hours perfecting a Cockney accent.

The six weeks flew by and as soon as they were up Davy took a train back to London. This time when he auditioned for the part of the Dodger, he got it. “It was funny,” recalls Davy. “They didn’t think I was the same guy. Well, they knew I was the same one, but they couldn’t understand how I’d learned that accent.

“I’ve just got the will to learn. And I wanted to make the grade. I was on a new kick. I was going to make money and I was going to act.”

So Davy began a full-fledged acting career on the very top—playing in a hit show on the famous West End of London. Actually Davy was one of an entire new cast for “Oliver.” After already playing two and a half years, the American producer, David Merrick, had arranged to take the original cast to America. After touring around the States, “Oliver” would then open on Broadway—so two Olivers would be going on at the same time, an ocean apart.

The London scene Permalink

Davy slipped with perfect ease into the new role. For seven months he worked, and loved it. He was completely free in a wild, swinging city. On his time off he’d wander around the city, meeting people, or just looking. He was making a fortune—about 45 dollars a week. “I was always used to earning 30 shillings a week. That’s about four and a half dollars, so you can imagine I thought it was quite a bit.”

The months passed and Davy had turned into a polished professional. Then another break came Davy’s way. The American “Oliver” was in terrible trouble and the producers were in a frenzy. The cast who were so marvelous in England were a disaster in America. People just couldn’t understand what was being said. The boy who played the Artful Dodger was a wonder, but his native Cockney accent was so thick that the audience just couldn’t understand a word. The producers finally got on a plane and beat it back to London to get a replacement.

A chance in America Permalink

One look at Davy and they knew he was it. “I talk slowly anyway, but I had to think about every word I spoke because Cockney was so foreign to me, so I really spoke slowly.”

Before Davy knew it he was on a plane and headed for the United States. “We landed in Toronto, Canada, where they were playing at the time. The next stop was the big time—Broadway. It was really wild. I’d never stayed in a real hotel before. I watched TV all day—in England it runs only between five and ten thirty, then it goes off.”

But Davy became a prisoner in his room. Already the cast’s nerves were to the breaking point. They had been together so long everyone was like a blood-brother, rather than an acting company. And the producers couldn’t bring themselves to tell the boy who played the Dodger that he was through…

While they tried to get the courage to tell him, Davy sat locked up in his room. The producers didn’t want the boy to even know Davy was there.

Opening night Permalink

On the fourth day Davy couldn’t stand it. “I told them off. I called them on the phone and said, ‘Listen, I’m going home to England, goodbye.’ Even though I was sitting there with a contract. I was really cocky. They came over straightaway and said they’d go ahead, and they did.

“When they told the boy who was playing the Dodger he’d have to leave, the cast was terribly upset. And without even knowing me they turned against me.”

It was a terrible situation and the strain of a Broadway opening night intensified it. Davy hadn’t tried to win the others over, he had just let well enough alone. And then opening night they came the full way around.

“I was still very green and very nervous. Opening night was a pretty, frightening event. After all, it was my first ‘opening’—Oliver had been going for two and a half years when I joined. My first lines came after the show had been going on for 35 minutes. I walked on stage, then, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a late couple walking down the aisle to take their places in the front row. I turned and said, ‘Oh, I’m glad you could make it, we’ve been waiting for you,’ or something like that, and it broke the audience up. I’d just gone straight out of character and started talking to these people up front, and they threw back beautiful lines which I could really handle. And then we went on with the show.”

A star is born Permalink

The show closed to thunderous applause. Everybody crowded around the stars, congratulating them, and Davy was left alone. All the cast took off for the gala party held after the show; everybody of importance, in and out of show business, was there. The festivities would go on into the early hours of the morning until the morning papers came out and the reviews of the night before read.

At the party Davy was again alone. The beautiful and important people seemed a million miles off to him. He even began to doubt himself. The party wore on to the wee hours of the morning; finally the papers arrived. “It was fantastic,” says Davy. “We opened the papers—and I’d gotten all the reviews! They hardly mentioned another person. They’d raved about me.

“But it was funny, I still didn’t feel like anything because until that moment nobody wanted to know me.”

Life in New York Permalink

For two and a half years Davy played on Broadway. People continued to rave about him; critics wrote that he was the greatest; fan letters showered on top of him, but it was as if the TV and movie people in Hollywood were completely deaf to all the raves… Davy might just as well have been back on the West End of London for all the good the reviews did him. “Nobody recognized the talent that all the papers said I had,” said Davy. “It was really frustrating. But anyway I loved New York and I gained all kinds of friends.”

One of Davy’s closest friends was Jim Downey, a wild robust Irishman, much older than Davy, who owned a restaurant where all the sports and theatre crowd gathered. Downey’s, was famous for its steak, and Jim’s personality. “Every Saturday night I’d go into his place and we’d sit and talk until way early in the morning. We’d talk about everything, but a lot about horses—he owned two thoroughbreds. At six in the morning we’d drive down to the stable and I’d ride. Then we’d go back home and I’d go to bed. I’d wake up about 11 at night and go back to Jim’s and have a late snack with him. Then I’d sleep until the show on Monday night.”

Except to go to Jim’s and walk around New York, there weren’t too many places for a 16-year-old to go. The legal drinking age in New York is 18, and Davy, who was always around older people, couldn’t really take a date any place. So his romantic life was at a very low ebb… then he fell in love.

His first love Permalink

“She was one of the Baker twins,” says Davy, with a fond smile lighting his face. “She wasn’t in love with me of course. I was a little kid to her, even though she was my age. I used to pop over and see her every night after the show, then maybe we’d go to Downey’s and have some spare ribs. And then I’d take her home. That was all there was to it.”

The one-sided romance broke up when “Oliver,” and Davy, had to go on the road again. In the meantime a single hint of what was to be in store for Davy happened. “Ward Sylvester, who was an important executive at Columbia, saw me and offered me a singing contract with Colpix, which is now Colgems.

“I made a couple of records that did nothing at all. Then I had one called, ‘What Are We Going To Do.’ It was a song like ‘Mrs. Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter.’ It made number 36 on the charts. As soon as it came out it was doing good because people thought it was Herman singing.”

Davy’s new manager Permalink

All Davy needed was one important person to really be interested in him and spread the word in Hollywood. Ward Sylvester was the person. At the time his word carried a lot of power, and he went back and told everybody about Davy. Screen Gems was interested, Columbia was interested, and they said they’d like to see Davy when he came to Los Angeles. But none of them were about to get on a plane and fly back to catch “Oliver.”

Then Ward made an unheard of move. Davy had so impressed him, and he had so much faith in the boy’s future, that he quit his job and became Davy’s personal manager. His pay was a percentage of what Davy was earning at the time—75 dollars a week!

One break followed another and Davy finally got the big chance to come to Hollywood and show them all how great he was—and he almost turned it down.

A new show Permalink

“David Merrick, the same man who produced ‘Oliver,’ asked me to do ‘Pickwick’ for three months. It was a fantastic part. But after three months they were bringing somebody over from London who was well known to take over my part. They asked me how much money I wanted. By this time, after three and a half years in Oliver, my salary was up to 400 dollars a week.

“‘I’ll do it,’ I said, ‘for 750 dollars a week for three months.’ Well, naturally they said in a nice way that I was crazy and they could never meet the price. The next day they were back, and the next and the next. Of course, the point of all this for me was to get to Los Angeles and have a showcase so people could see me. Finally we settled on a price. That was Saturday afternoon and they were starting rehearsals Monday. I flew back to New York on the next plane and played in ‘Oliver’ that night—for the last time. Between the shows I went home and packed my things. I caught the 1:30 a.m. flight to Los Angeles and Monday morning started rehearsals.”

For three months Davy played San Francisco, getting ready for the all-important two month date in Los Angeles. Ward was with him all the time, helping, advising. Then the show opened in Los Angeles to wonderful reviews. “Ward and I were paying to bring everybody to the theatre. I had everybody in Hollywood, even Walt Disney, come to see me.”

The big break Permalink

One night some writers from Screen Gems saw him and went back to the studio raving about the fabulous Davy Jones. Suddenly Davy had four TV pilots offered to him. Screen Gems rushed him into a seven year contract worth 300,000 dollars. “It was fantastic money and all the papers in England wrote it up. I was suddenly famous at home.

“One of the pilots they offered me was great and who knows, I might yet do it. It’s about a policeman and a leprechaun. Only the policeman can see the leprechaun. He gets into situations and I get him out of them—sort of like a ‘Bewitched.’

“Then they shelved that for awhile and decided that the thing to do was to write a brand new series idea. They had me on retainer—and shipped me out to do spots on different TV shows. On a Ben Casey I played a married guy who sniffed glue. So I just played myself and then cracked as if I sniffed glue. But I don’t want to get out of character like that again really.”

What is a Monkee? Permalink

“I don’t want to improve my acting. Actually I learn things every time. I act, but I don’t want to take lessons or anything. I put myself in the part that I play. I don’t want to have to go out and play a glue sniffer that beats his wife.

“I did a lot of rock and roll shows that Screen Gems wanted me to do. Ward and I were living on North Ivar (in Hollywood) at the time, in a little apartment with a living room, two bedrooms and a kitchen as big as a chair.”

While Ward and Davy lived together Ward introduced him to all the VIP’s at Screen Gems—the people who most new contractees never even catch a glimpse of. And he met Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson. A few days after that historic meeting they approached him with a new series idea called “The Monkees.”

“I was still really green as far as business goes,” recalls Davy. “I read the script and said yeah, it was great. But you know I wasn’t thinking about when they’d really do the show; I just read what they had written down.”

Screen Gems gave them the green light for the series. Now that Davy’s part was decided all they needed were the three other Monkees. What happened then is history. They advertised for “four insane boys” and 400 actors showed up. And they interviewed every last one of them.

Mike’s laundry bag Permalink

“Mike really cracked me up when he came in,” says Davy. “He walked in with his wool hat, blue jeans and a western shirt, and a laundry bag with his laundry in it—he was afraid to leave it in his car. When Lester (Sill) asked him if he had any pictures, he said yes. And he was told to go home and get them and come back. He was back in 15 minutes—and he was still hanging onto the laundry bag. He just broke me up.

“They were also interested in a couple of guys who turned the show down. One was Jerry Yester (he was with the Modern Folk Quintet, and now is the new addition to the Lovin’ Spoonful), and Steve Sills of the Buffalo Springfield. They liked Steve very much but he turned it down. He said, ‘That’s not my bag, it’s not what I want to do. But I do have a buddy—a friend of mine who’s working out at Santa Monica in a coffee shop washing dishes; he plays guitar for his food.’

“So Peter came down in blue jeans that were really dirty, his hair all over the place and unshaven. Then Bert really flipped for Peter because of something he did. Peter went to sit down and he pulled the chair out from under him. So Peter calmly walked over and pulled all the things off the desk. Then he said as if nothing had happened, ‘Do you want to get started now?’, or something like that.

“They narrowed the field down to ten boys, including myself. We all had to take screen tests. Then they got us down to six. Myself, Peter, Micky, Mike, Bill Chadwick, who’s a song writer and a great friend of mine, and a drummer.”

They left the final decision up to the public. They took all the tests to the “Preview Theatre” on Sunset Blvd.

The winners are picked Permalink

This unique theatre is open to the public and screens everything from TV commercials to untested pilots. Then through various methods they test for audience reaction. The Monkee’s producers asked the audience to list the boys they like the best in the order of preference. It’s interesting to note that Davy walked away with first honors.

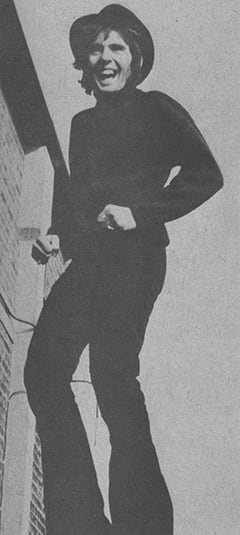

But when Davy was told he had the part he started having serious doubts about how well he fit into the new series. “I looked at a lot of groups,” says Davy, “and I went into Bert and told him I didn’t want to do the show. I didn’t think I was right for the part. Most groups are all alike—the same height and all. There’s nothing greater than to see four guys all the same height in the same suits, like the Beatles. Ringo’s a little shorter than the others but he still doesn’t look as short as I do with our group. I said get somebody else who’s better. There are still three other screen tests I can do. I can do anything…”

All individuals Permalink

“But Bert said, “That’s exactly what we want, man. If I were to put a paper bag over your head and stand you next to the three other guys I want everybody to know who’s under each bag. We want four indivduals [sic].’

“And he really got four individuals. We couldn’t be further apart. I’m from England, Peter’s from Connecticut, Mike is from Texas and Micky is from Los Angeles. Our musical ideas are unbelievably different… and it’s taken until now, two and a half years later, to do what we really want to do musically.”

Because the producers wanted all fresh, young ideas they chose Jim Frawley as the director. He’d never directed before; he was an actor who had produced a couple of underground movies. But with The Monkees everything was a first. When everything was all set for the pilot, the director, crew and the four brand-new Monkees flew down to San Diego to shoot the first sequence.

A complete disaster Permalink

“We shot it, and they put it together. When I viewed it I knew it was the worst thing I’d ever seen in my life,” says Davy. “It was just garbage. Nothing worked; the funny parts weren’t funny. It just didn’t go the way they had wanted it to.

“Then they had to show it to the other bigwigs. They got halfway through the screening and had to leave to get sick. They said, ‘You must be joking.’ There was so much money in it, and it was worthless.”

For three months they tried to sell it to anybody. They doctored it up and doctored it up but no one was buying. Then it happened.

“I’ll never forget. It was a Thursday night. The studio was showing pilots the next night to sponsors. There were ten pilots at Screen Gems and they knew six of them would be sold. Ours wasn’t one of them. In fact it wasn’t even included in the ten to be screened. Raffelson [sic] went to a big shot and begged to be given until Monday to change the pilot again. But he was refused. Then he said, ‘Give me until tomorrow,’ and he was refused again.”

The miracle Permalink

“So Ward and he went home to that apartment on Ivar, cleared the living room of the furniture and started to work. Spools of film were spilled out all over the floor. They cut each sequence with scissors and then stuck them back together like they wanted with cellophane. They recut the whole thing and it took them until the next morning. They took the finished film back up to the head office and said, ‘You’ve got to let us show it.’ Finally they consented and it was sold that night. They had performed a miracle!”

In the meantime Davy, tired of the whole mess, had flown back to England. He’d even gone as far as renewing his jockey license. “I had all my things packed, ready to leave for the stables and I got the call from Mike. ‘Come on, Davy, you’ve got to come back,’ he said. “We’re going to do the show. But I said no, I’d been waiting for two months for them to contact me and they hadn’t so now I was set on returning to the stables. Then I asked Mike if he were going to do it and he said, ‘Yes, I’m doing it, it’s going to be really fantastic.’ He was really excited. So I came back.”

But after the shooting of the pilot there were the three months of no work—and no money. All four of the Monkees were really down and out.

The poor Monkees Permalink

“We were broke all the time then,” says Davy. “I remember I used to take Peter out to lunch and he always used to say, ‘One day I’m going to pay you back.’ I told him not to worry, that he’d have plenty of opportunity. I had saved a little money from ‘Oliver’ and that’s what I was living off of at the time. During the screen test I would take them all out to lunch—they couldn’t get over it.

“And Mike used to invite us all up to dinner. Phyllis would cook—and she’d cook big. If Mike had 10 dollars he’d go out and buy 10 dollars worth of food. He’d have five or six people and they’d have the best steak, the best vegetables and a wonderful dessert. Phyllis would manage to make it on that. And then they’d eat canned food for the rest of the week. That’s the type of guy Mike is. He’d spend his last dollar on somebody. He just bought his brother-in-law a $3,000 car, and he bought his best friend a Buick Riviera. It’s really great.”

Monkee music Permalink

“During that time Peter was living at Mike’s house. A couple of them borrowed a couple of hundred dollars from Screen Gems, but the studio was really tight.

“And for the three months we practiced our music. When you don’t know a thing about music it’s a little hard keeping the beat. I had never even picked up an instrument, but Mike, Micky, and Peter were great on the guitar. We just played for something to do, and Screen Gems rented the instruments for us. We decided someone would have to play the drums and Micky volunteered though he really couldn’t play them—he couldn’t keep the rhythm. And Peter got to be the bass guitarist because Mike didn’t want to play it.”

Then their record producer (Don Kirshner) took the music situation into his own hands—to the dismay of the boys. He hired studio musicians to do all the music tracks, and then he told the boys that once the music was recorded, they would sing over it. “We said great,” says Davy. “But then he recorded songs that none of us particularly liked. It just wasn’t what we wanted. I’d always heard that a group did the type of songs that they liked doing. But they decided they knew what was best. Well, it took an album and two singles before we got to do our own stuff!”

The Monkees today Permalink

“It’s weird,” continues Davy. “You see seven-, eight- and nine-year-olds at our concerts; it’s such a young appeal we seem to have. They’ve all been waiting for something to scream for for the last five years. The Beatles were too old for them when they first came out, and there’s been no group that’s made it big enough so they can identify. That’s why the Monkees made it. Because we’re catering to the kids. So whatever we play is Monkee music… I sometimes think we could record Happy Birthday and sell it.

“It’s great, all this time we’ve waited to do our own stuff, and now we’re doing it, and we’re doing it the way that we feel, yet we’re still catering to the kids and allowing them to buy the records—to understand.”