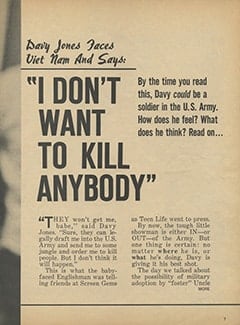

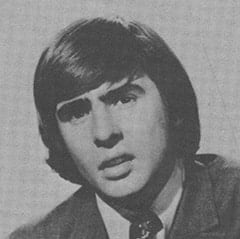

By the time you read this, Davy could be a soldier in the U.S. Army. How does he feel? What does he think? Read on…

“They won’t get me, babe,” said Davy Jones. “Sure, they can legally draft me into the U.S. Army and send me to some jungle and order me to kill people. But I don’t think it will happen.”

This is what the babyfaced Englishman was telling friends at Screen Gems as Teen Life went to press.

By now, the tough little showman is either IN—or OUT—of the Army. But one thing is certain: no matter where he is, or what he’s doing, Davy is giving it his best shot.

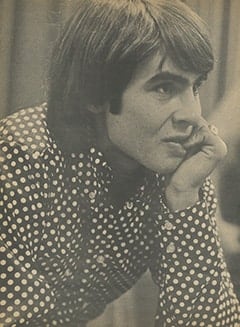

The day we talked about the possibility of military adoption by “foster” Uncle Sam, Davy was busy on the Monkees set. He had bounced through a rough scene without a flub, and seemed especially pleased with himself. He laughed more than usual, bursting into giggles. And then I sensed the nervous tension.

Unlike his partners, Davy kids around more when he is troubled. When Mike Nesmith or Peter Tork want to avoid certain subjects, they will say so. When Micky refuses to answer he always explains why—which is usually the answer. But Davy’s evasions are in the form of games and nonsense.

“See that chick over there?” he was saying. “That’s Joy Harmon. She’s in this show. Look at that blonde hair!”

He was avoiding the direct question: “Have you taken your physical?”

“…blondes like that are a gas,” he sighed.

I repeated the question. This time he heard it.

“Physical? What for? Y’mean the Army physical? No, I haven’t. I don’t think it’ll come to that.”

Micky Dolenz joined in.

“Hey, Davy, remember that guy who wanted to pass out bumper stickers?”

“Yeh,” answered Davy, “but no one thought they were funny ’cept him, poor jerk.”

Micky recalled one bumper sticker which said: THERE ARE NO MONKEES IN FOX HOLES—based on a World War I slogan often heard at religious gatherings (“There are no atheists in fox holes”).

“It’s NOT funny,” grumbled Davy. Micky shrugged and walked off.

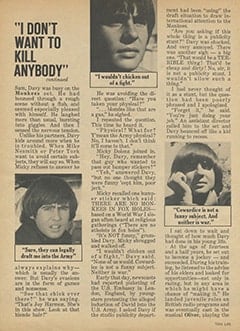

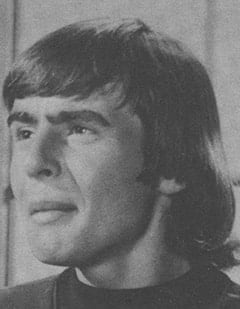

“I wouldn’t chicken out of a fight,” Davy said. “None of us would. Cowardice is not a funny subject. Neither is war.”

Early that day, newscasts had reported picketing of the U.S. Embassy in London, England, by youngsters protesting the alleged induction of David into the U.S. Army. I asked Davy if the studio publicity department had been “using” the draft situation to draw international attention to the Monkees.

“Are you asking if this whole thing is a publicity stunt?” Davy was shocked. And very annoyed. There was another sigh—a big one. “That would be a TERRIBLE thing! That’d be cheap and dirty! No, sir, it is not a publicity stunt. I wouldn’t allow such a thing.”

I had never thought of it as a stunt, but the question had been poorly phrased and I apologized.

“Forget it,” he said. “You’re just doing your job.” An assistant director called him to the set and Davy bounced off like a kid running to recess.

I sat down to wait and thought of how much Davy had done in his young life.

At the age of fourteen and a half years, he set out to become a jockey—and succeeded. During his training, he listened to the advice of his elders and looked for opportunities—not only in racing, but in any area in which he might have a chance of “making it.” He landed juvenile roles on British radio programs and was eventually cast in the musical Oliver, playing the part of the Artful Dodger.

When Oliver moved from London to Broadway with the original cast, Davy was going on seventeen. He has been a working visitor in the U.S. ever since. Obviously, he carries a work permit and has paid his share of income taxes. But does that give Uncle Sam the right to make an American soldier out of him? Well, the answer to that is that it does. And Davy knew when he came here that he’d have to register for Selective Service, just like any other young man of draft age.

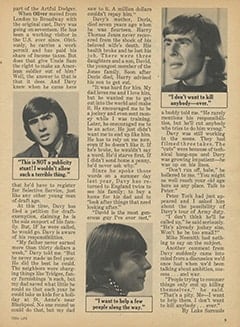

At this time, Davy has filed a petition for draft-exemption, claiming he is the sole support of his family. But, IF he were called, he would go. Davy is aware of his responsibilities.

“My father never earned more than thirty dollars a week,” Davy told me. “But he never made us feel poor. He did the best he could. The neighbors were charging things like ’fridges, fancy furnishings ’n such, but my dad saved what little he could so that each year he could take us kids for a holiday at St. Anne’s near Blackpool. No one round us could do that, but my dad saw to it. A million dollars couldn’t repay him.”

Davy’s mother, Doris, died seven years ago when he was fourteen. Harry Thomas Jones never recovered from the shock of his beloved wife’s death. His health broke and he lost his job. There were three daughters and a son, David, the youngest member of the Jones family. Soon after Doris died, Harry advised his son to get out.

“It was hard for him. My dad loves me and I love him, but he wanted me to get out into the world and make it. He encouraged me to be a jockey and even sent money while I was training. Later, he encouraged me to be an actor. He just didn’t want me to end up like him. He has to rely on me now, even if he doesn’t like it. If he’s broke, he wouldn’t say a word. He’d starve first. If I didn’t send home a penny, he’d never ask why.”

Since he spoke those words on a summer day last year, Davy has returned to England twice to see his family; to buy a home for his dad and to “look after things that need looking after.”

“David is the most generous guy I’ve ever met.” a buddy told me. “He rarely mentions his responsibilities, but he’ll cut anybody who tries to do him wrong.”

Davy was still working in the scene. They had filmed three takes. The “cuts” were because of technical hang-ups and Davy was growing impatient—he was up on his lines.

“Don’t run off, babe,” he hollered to me. “You might as well reach your old age here as any place. Talk to Peter.”

Peter Tork had just appeared and I asked him about the possibility of Davy’s tour of Army duty.

“I don’t think he’ll be called up,” he said seriously. “He’s already jockey size. Won’t he be too small?”

Mike Nesmith had nothing to say on the subject.

Another comment from Davy suddenly came into mind from a discussion we’d once had when we’d been talking about ambition, success… and war.

“People trying to conquer things only end up killing themselves,” he said. “That’s a pity. Me—I want to help them. I don’t want to kill anybody… ever.”.