(It’s late afternoon, Sunday, November 16, 1986. It’s cold and raining in Pontiac, Michigan, where the Monkees are scheduled to play tonight. The last time they were in Michigan, they played an outdoor venue on a beautiful summer evening. Tonight, they’re playing the Pontiac Silverdome, a cavernous, enclosed stadium where the Detroit Lions frequently bang heads. The last entertainer to perform there was Bruce Springsteen and his E Street Band. I’m skeptical, but—as I shall later see—the Monkees manage to pull it off with flying colors.

I’m scheduled to interview the Monkees at the Troy Hilton, spending a half hour with each of them in their hotel rooms. The Monkees may have lived and loved together in that house on your TV screen during the ’60s, but it’s apparent in 1986 that the Monkees are really separate individuals who just get together nightly to form an incredibly entertaining musical-comedy group. Since the tour began, each Monkee has had his own tour bus. Micky and Davy travel with their families, while Peter is on the road with his girlfriend, Jennifer. I’m supposed to interview the latter Monkee first.

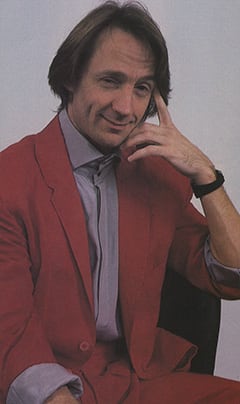

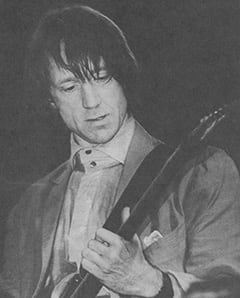

There is a “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door. “Oh well,” I think, and knock anyway. The door opens, and Peter Tork is standing there. He smiles. And then it hits me. When I was 10 years old, if someone had told me I’d someday be a rock writer spending an afternoon with the Monkees, I probably would’ve told them that means I’ll accomplish everything I ever wanted… Of course, growing up changes everything, but I still think this is pretty neat. Despite the rumors of a rough post-Monkees life, Peter looks great, just an older version of the guy on the TV screen—although, as I shall see, all the Monkees look pretty tired. It’s been a long, hectic tour.

Peter introduces me to Jennifer, and we sit at a table, where he proceeds to drink a lot of coffee (he says he always mixes in half decaffeinated). Of all four Monkees, Peter’s onscreen persona was the least like his real self. The “dumb” (albeit bighearted) Monkee is actually soft-spoken and a bit on the philosophical side with a dry sense of humor. He thinks about every word he says. What follows is pretty much a verbatim transcript of our conversation.)

Bill Holdship: I wasn’t sure I should knock. You had the “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door.

Peter Tork: Oh, that’s just so the maids don’t come in at the crack of dawn. (In a high pitched voice) “Housekeeping.” Sometimes they do it anyway.

You have a whole bunch of young fans waiting out there by your tour bus. Has it been the same in every city?

Tork: It’s been a little excessive lately, the last couple of days. Mostly, they’re a little bit better behaved than that, that is to say a little more reticent. That’s not the word I’m looking for either. Sedate? What’s the word I’m looking for?

Jennifer: Less grabby? (laughs)

Tork: Our words are being recorded, Jennifer.

Jennifer: Oh, well, I was just kidding.

Don’t worry. I like the Monkees. I won’t make you look bad.

Tork: I don’t know that that makes for good journalism.

(Laughs) I just wrote an article on you guys for CREEM called “I Like The Monkees.” I saw you guys for the first time at Olympia Stadium in Detroit when I was 10 years old. I’m a big Monkees fan, so it’s an honor to be talking to you guys. I haven’t been nervous about talking to a rock star in years, but this is like a real exciting thing for me.

Tork: Well, thank you very much. You’re nervous, huh? How can we exploit this? Is there any way we can use this?

I’m sure you’re asked this all the time, but did you expect this huge phenomenon that the Monkees’ reunion has created?

Tork: No. Not to this extent. I must say that we certainly expected a lot of it. We certainly expected to do well, but we did not expect to do this well. When the tour was originally proposed to us—the terms, the set-up and the style—we knew it was going to be much bigger than (promoter) David Fishoff thought it was going to be. We were dead certain, dead convinced of this. Partly because David Jones and I had just been in Australia, and we’d done very well there. The TV show wasn’t running there, and there wasn’t any MTV or anything like that. We were putting this current tour together before MTV. We’ve been talking about this since at least August of ’85. And we kept trying to convince David Fishoff that it was going to be bigger than he kept saying it was going to be. But it’s turned out to be even bigger than we thought it was going to be. We’ve certainly got to say thanks to MTV for a lot of it. Exactly how much, I mean, who can tell? But certainly a lot of it.

I want to ask you some questions about the old days, especially the music. We’re a rock ’n’ roll magazine, so that’s what we’re most interested in. You guys actually did play on Headquarters, right?

Tork: Yeah, that’s us.

That’s my favorite Monkees’ album.

Tork: Great. We loved it. I liked it a whole lot because I thought that it was “living” in a sense the other albums weren’t. The other albums may have been much better, but there’s something about the quality of studio professionals. I should say unengaged studio professionals. You get very good product out of those guys, studio session people, but they don’t have time… or they cannot allow themselves to pass judgement too much on what they’re playing because then they wouldn’t be able to play the bad stuff they’re required to play. So they have to reserve judgement to a certain extent. And as much lower as the technical level was back then—and it was a lot lower—still the fact that it was really us, actually working on it… well, it was a pretty good first album, if you know what I mean.

It was a great first album. “Shades Of Grey” is one of my favorite songs to come out of the ’60s.

Tork: Well, now the material is a different kettle of fish entirely from the recording. You can’t fault the material. They generally say that it’s too frothy and not committed enough, but I mean you could chastise Dylan for not being Shakespeare just as easily as you could chastise us for not being Dylan.

Who chose the Monkees’ songs at that point? I know that Kirshner chose them until Headquarters, but after that, you guys pretty much chose what songs you wanted to record?

Tork: Oh, yeah. It was all right there. I mean, we still had access to the same number of people, and, by that point, we’d gotten a pretty good idea of what a good pop tune was all about. We did have the master to learn from, after all the man with the golden… I don’t know what. The golden thyroid.

On the first two albums, did you guys play on any of Mike’s stuff?

Tork: I played fourth chair guitar on one of Mike’s cuts, I think.

You guys took a lot of criticism in the ’60s for being “manufactured.” Did it bother you? When I interviewed Micky last summer, he said it never really bothered him all that much. But I always got the impression that you and Mike, as musicians, were a little more hurt by all the criticism you got from the press.

Tork: Yeah. Yeah, I was. I don’t agree with me now. I don’t agree with that view now. I think everyone was subject to the same notions, and they’ve [sic] very valuable notions, but I think they were misplaced under the circumstances, although there’s a couple of them flying around loose still. One of them is that any time anything like this happens, there’s going to be a lot of flak. You just cannot do anything like this without meeting resistance. Then there’s the issue of “pure as the driven snow,” and was it ethical and moral and all that kind of stuff. I must tell you that for a couple of years I thought it was the musicians who were angry at us, while the actors thought that we were doing a pretty decent job. I later discovered that the community of young off-Broadway actors in New York City thought that the music was fine, but as far as acting goes, we were four talentless shlemiels who they yanked off the street, out of the gutter, and it could have been any four guys. And that’s exactly the same thing the musicians were saying about the music. So that led me to just decide that it was all part of the same resistance. Any time something like the Monkees happens, you get that kind of backlash.

But as far as the validity of the standard goes, I don’t know how useful that standard is in all cases. One of the features of the ’60s was kind of an all-or-nothing approach to matters; that is, you either conformed to the moral standard or you didn’t, and they [sic] was very, very little gray area. I think that was probably very important, but I think it was also a idealistic generation making its first foray into moral judgement, and your first foray into moral judgement is always black or white. It’s just the way it goes. At at that level, at that time, in that field, we were victims because, again, I don’t think that the question of whether the Monkees should’ve conformed to the moral standards set by the Beatles was a fair one. It wasn’t. We weren’t being the Beatles, and we never said that we would be. We never said that we were going to be the Beatles. What we were is what we were. Which I look back on it now, and I think we were unique. We still are. And I think we’re to be judged by the standards that we set for ourselves. And that’s not to say that we could do no wrong. That would be nonsense. But whether we behaved well within our own moral code is what we’re to be judged by.

I think the most important thing is the music you produced then still holds up with anything that came out of the ’60s. Plus, there are a whole lot of bands today that are doing “worse” things than what the Monkees were accused of at the time.

Tork: Yes, that’s true. And I think that’s the final chapter on that whole story. And no one’s giving us any of that type of criticism anymore. I mean, people mention it, but I have much less of a sense that that counts for much of anything in anybody’s mind anymore. It’s a dead issue. Nobody really cares. Imagine what would happen today if just the three of us tried to go out there and play our stuff. I mean, when the four of us went out and played it sounded pretty stark and spare. Three of us are going to be pretty loose, unless you got a magical box out there that can reproduce a symphony orchestra. So we take a rock band and horns out with us these days. You know, we use pros. No reason not to.

Well, like I said, I think you guys proved you could cut it on Headquarters. Do you think ’60s music was better than the music that’s being produced today, and that’s why the ’60s are coming back as nostalgia?

Tork: No. No, I don’t. I think the music is actually about the same. It seems that such subtle and sophisticated issues as chord patterns and even lyrics are about the same now as they were then. And what seems to count most of all—then as now—is a kind of a combination of skill and commitment. It’s a balance kind of a thing. You can do with a little less commitment if you got a little more skill, and vice versa. But without one of the other, you can’t do anything. You gotta have some skill and some commitment. You know, one of the most engaging cuts that I’ve heard in a long time is “Wake Me Up Before You Go Go.”

By Wham?

Tork: Yeah, by Wham. And I’m not at all fond of George Michael’s persona. What I see on the screen and so on is not at all to my liking. But that record is full of pulse and beat and leap. A lot of drive to it and a lot of impulse. (At this point, the interview is interrupted by a phone call.)

How do you feel about the Monkees’ place in rock or entertainment history? It seems pretty secure now, don’t you think?

Tork: Yeah, unless we fuck it up (laughs).

Is it tough being on the road all this time like this?

Tork: Oh, yeah, it’s murder. How long have we been on the road now?

Jennifer: Basically since February 10th.

Since February 10th?

Tork: Well, that includes Australia, with Jones and me. I’ve been on the road with this since the middle of May, counting rehearsal time.

So it’s going to conclude now for the holidays?

Tork: Yeah, it’s going to conclude for the holidays. From then on, it’s other projects, none of which are totally defined right now. But we’re hoping to do albums, movies, TV specials. We might even do a Broadway play.

I heard about that. You may do a revival of an old play?

Tork: Yeah. We’ve read scripts, but one script is right up our alley. I hope we do it just for the sake of getting to do it. It would be great to have that in my resume. Jones, whose had experience in the theater, tells me that it’s a life that’s about as tough as this one—and I don’t know how long I can carry on a life as tough as this, although I’ve always thought the travel is the worst part, and that’s one thing we wouldn’t have with a Broadway play.

Is it a revival of a Marx Brothers play?

Tork: No, but it’s similar in style. It may even be wilder. I don’t really want to say much more than that, because it hasn’t been confirmed at the moment.

How is life on the road today compared to life on the road in the ’60s? Is it similar or is it a totally different scene?

Tork: Well, we have a tougher schedule. And I have less resilience, being this much older. Those two things add up to a little bit more of a grind for me than was previously the case. But it’s not really a great big deal. It’s alright.

You directed an episode of The Monkees, right?

Tork: Yeah.

Did you do any film or TV directing after that?

Tork: No. I just had the opportunity to watch that show again, and the first couple of years after I made it, I thought I’d done a real good job. But now it looks awfully episodic. So I don’t know what kind of a director I’d be today if I’d have kept at it. But I’d like to try my hand at it again someday.

A lot of the stuff in the show was pretty impromptu, right? You’d just have a storyline, and then there’d be a lot of ad libbing?

Tork: No. Actually, most of that stuff… well, they had to write us a half hour TV show. What we did do was if we thought a particular joke didn’t work or a particular bit didn’t work for whatever reason, we would request to change it. Now, we were given permission to change it as long as a.) we didn’t step over any of the constraints—kick over any of the censorship things—and b.) it advanced the plot the same as the other joke or bit did, and c.) if we had the props for it. I mean, you could have this great bit, but if you didn’t have the props for it, you were sunk. Fortunately, the props were very well-stocked in general, so we could come up with an awful lot of bits. But then we had to rehearse the new joke, so what finally hit the screen was almost always rehearsed. Once in awhile, we would go off the deep end and make an extra little ad libbed comment. But, by and large, almost everything you see was set up at least just before the shot. But we were given some fair amount of freedom. They wanted us to be able to do what it was they hired us to do—which was to be funny. So if we came up with something funnier than what they had, they were awfully glad to have it.

One of the things about the Monkees’ charm was that you guys always seemed “approachable.” I think that’s why little kids like the Monkees so much. You guys seemed like you could’ve lived next door, whereas the stars of today keep their distance. You’ve got the Princes and Madonnas on their pedestals. Do you think that’s a valid point?

Tork: Well, yes, of course—but I think the reason for that has to do with the TV show. If Prince were doing a situation comedy on a regular basis, whatever character he played, the kids would think that’s who he was—and they might think he was accessible as a next door neighbor in that character. That’s what happened to us. If we had been doing high style drawing room comedy on a very occasional basis, we’d have probably been regarded as aloof and almost untouchable. But I think a lot of it had to do with the setting and the format of the show. And, of course, the whole thing about the Monkees is that we’re not too swept away with form. At one point on this tour, we came to the end of a number, and usually one or another of us takes over and conducts the end of the song. Micky and I almost at once turned to Davy, and there was Davy waving his arm—and we thought, “Davy’s going to end it.” Davy, instead of leaping in the air in a typical rock gesture, fell flat on his ass. (laughs) So, you know, with that kind of an attitude, we couldn’t carry off an air of aloofness with any kind of success. Although I’m actually a total and absolute snob. And very unapproachable.

Yeah, well you’ve always seemed that way, I must say.

Tork: I deign to notice the peons only on the rarest of occasions.

Did you guys get along? Was there any resentment between the Monkees? I mean, you spent so much time together, but it was like you always stayed friendly. Even the Beatles didn’t accomplish that.

Tork: Well… sure, we were friends. Sure, we had resentments. I mean, that’s life, you know. We were human beings there. Ask anyone if they don’t have some resentments against their co-workers and if they don’t occasionally not get along with each other. You have co-workers, and you’re going to have some resentment there. That’s life. How about you?

Sure.

Tork: Well, that’s life.

That’s fair. I just saw a letter in Rolling Stone. Someone wrote in and said the great thing about the Monkees was that it was good, clean fun.

Tork: (Fakes an uproarious laugh) I’m sorry.

It said you didn’t discuss politics, you weren’t subversive. I tend to disagree with that at some levels. Timothy Leary made that statement about you guys. And then there was Head, which was sort of subversive in its own weird way.

Tork: Well, subversive maybe in form, but not in content. That was perhaps the saving aspect. The thing that I remark on a lot these days is that originally the Monkees were seen as a situation comedy about young adults with no authority figure. And that was unique on television at the time. I think that’s one of the reasons why we’re successful again today. You have the same situation now as we did then in that there’s a man in the White House who is often wrong but never in doubt. And I think the whole point of The Monkees was that we’re in some ways a self-dependent rather than an authority-dependent type of people. Which I think properly reflects the real American spirit, at least as far as I—in my extreme pomposity—understand it.

With all the projects coming up in the future, is there a possibility that Mike will do something with you as a group?

Tork: Mike will almost certainly show up, whether he plays a full quarter share or whether he does a cameo or something. We haven’t quite figured that out yet. Part of it depends on his schedule. And part of it depends on the kind of thing we want to do next. He’ll definitely be in on the discussions right from the get-go. But what exactly he does is up in the air yet.

How about the “New” Monkees? What do you think about that idea?

Tork: I’m personally a little confused about it all. There’s a political story behind it all that leaves me totally bewildered. There’s already been some confusion. In a recent newspaper article about the “New” Monkees, it was said “And you can see them tonight at such and such a theater”—and we were the Monkees at that theater. So there’s already some confusion, which is a little dismaying. On the other hand, I certainly don’t wish anyone ill. If they can bring it off, more power to them.

I personally think it’s a bad idea with no imagination behind it. I heard the producer saying it’ll be the Monkees for a new generation, but a lot of your fans are 13, 14, 15 year-olds, which is the new generation. They should’ve just invented a band with a new name. I think it’s a bad idea.

Tork: Well, a lot of people seem to think so. I feel obliged to maintain a little distance from the controvesy [sic]. I don’t want to… I mean, I have enough troubles of my own. That’s what it comes down to. I don’t want to get involved in any of this stuff.

When did you originally feel the bubble bursting with the Monkees? Right after the show ended?

Tork: Well, I didn’t. For me, it never was a case of the bubble bursting. It was much more a case of leaving the bubble through the airlock as it slowly fizzled away. I only see this in retrospect. At the time, I wanted to get out because wanted to be a Beatle-type musician. I wanted to lead my own band. I had no idea how difficult that was at the time. I just wanted to go off and do my own things. Now I wonder about my attitude then. I think it was probably a false attitude. On the other hand, if I’d been wiser, I might have left earlier. There’s no telling. Like I say, I didn’t have any sense of the bubble bursting. I just walked out of it. I mean, I had the bends for awhile coming back into re-entry, but it wasn’t like the bubble bursting in that I didn’t have a sense that one moment everything was flying high and the next moment everything was miserable. Because I myself did not change my sense of contentment. I found—and I have found consistently—that my sense of contentment has virtually nothing to do with my success. I was very content during certain periods with the Monkees. I was very happy at times, and I was miserable at times. I was happy afterwards sometimes, and I was miserable sometimes afterwards. And the history of my life has almost nothing to do, I’m talking about internal history, the history of my happiness—it has almost nothing to do with the history of my worldly success. So I didn’t have any sense of the bubble bursting. It was just my life carrying on, step by step.

So it wasn’t real difficult dealing with being “an ex-Monkee”?

Tork: Nah. No. What I did was… well, I spent a couple of years in L.A., and then I went up to Marin County, and I became engaged with a community up there. That was a community where I had very little sense that being an ex-Monkee mattered one way or another. I joined a few groups here and there. I was a member of a gospel… I call it an Aquarian age gospel choir. It was comprised of 35 voices, and I was just one of the voices in the bass section. And I was just knocking around the streets of Marin County, part of the Fairfax community, which was a flourishing, small, obscure but wonderful community. So, no, there was no partioular [sic] problem that I can recall being an ex-Monkee.

Of all the Monkees, you seemed to be the one most involved with ’60s lifestyles—the Greenwich village hippie scene, later the commune scene and all. You pretty much lived the whole thing.

Tork: Uh huh. That’s not a question. OK.

Are you still friends with Stephen Stills?

Tork: I haven’t seen Stephen—except very briefly—in 15 years. I saw David Crosby recently, and it is a joy to see the man. A joy. A positive thrill to see the man coherent and able to string sentences together and happy to be drug-free. And, of course, we have a similar history, although it wasn’t to the same degree. I had a history of chemical abuse and drug addiction as well. And I’m enormously happy, in my case, to be drug and alcohol free as well. And to see David that way is one of the great treats of my recent life. I saw Graham Nash at a Crosby, Stills & Nash concert a couple of years ago, and he seemed to be very well put together. And I would say that he’s still a friend of mine, although not a good friend in the sense that you look people up and hang out with them. I would not say that any of the major figures of those days and I are still friends, mainly because most of them are dead. The kinds of people I’m friends with from those days are people who—oh, I don’t know. It’s like I said, the business about worldly sucess [sic] and personal life has very little and almost no correspondence whatsoever. And that applies to the people who are your friends. If I sought my friends out because they were famous, you know, I’d be guilty of the same thing that I hate in other people. And I would be hinging my own life to popular success. And, you know, if you hook your life to any material thing, it’s going to take you up, but it’s eventually going to take you down. You have to hook your life to spiritual values, ’cause that’s the only thing that can continue to take you up indefinitely.

Well, you seem to be happy these days.

Tork: Yes, I am very happy. I’m about to have an attack of hysterics, hysterical delirium. Joy. I’m going to leap on the wall. You’ll have to peel me off the wall from my joy. I’m so goddamn happy I can’t stand myself.

(Laughs) How long do you think the Monkees are going to go on in this form? Indefinitely?

Tork: Well, there’s no telling. If all goes well, I think we can count on another year easily. Actually, there’s no way of telling. Let’s just put it that we can only plan a year or so at a time at this point. We cannot make a five year plan or anything. I think we can safely plan a year, and I would really expect at least another year or two after that. And maybe—what I sort of think in my mind is going to happen—we’ll go on indefinitely intermittently. We’ll do a short concert tour here, we’ll make a TV variety special there, make some public appearances, and fill in the rest of the time with our personal projects. We all have things that we’d like to do on the side. Davy Jones is, you know, theater born and bred. He just loves the theater. I love rock and folk, and entertaining in small clubs. Micky Dolenz wants to direct, and I wouldn’t mind doing that either.

Well, it’s great seeing you guys back. It really is.

Tork: Thank you very much.