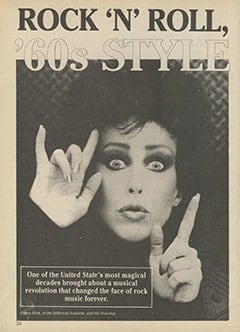

One of the United State’s most magical decades brought about a musical revolution that changed the face of rock music forever.

It was in the fall of 1963 that many think it began. The biggest segment of the population in America was the group from 15–18. But they weren’t quite a together force yet. Then, just before Thanksgiving of that year, things began to happen. Fast. President Kennedy was killed in Dallas on November 22 and a stunned nation began looking for an answer. That answer came in the form of four young men from a tiny shipping town in Northern England called Liverpool.

When the British invasion hit full swing in 1964–65, it was the beginning of a time that would bring a change in everything a sleepy America had become used to. There was new music in the air, new fashions, new ways to think about living life. It was, as many remember, a magic time.

The British Invasion took over America with a vengeance in the form of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Searchers, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Herman’s Hermits and so many more who shared a fresh new sound. In 1965, Life Magazine estimated that two out of every five boys in the country were in a band of some sort. It was the kind of feeling the music scene wouldn’t see again till the Punk revolution of the late ’70s. There was that magic feeling that anyone could be in a band. And they were.

In the mid-’60s, new groups seemed to appear every week, groups that would have one hit record and then disappear. Bands like the Outsiders, The Blues Magoos, the Electric Prunes, the Seeds, The Leaves, and the Strawberry Alarm Clock, though it was LA’s Doors who made a lasting impression.

Most of these new groups took their cues from the “hippie” scene that was quickly growing in America. They sang songs about flowers, about love, and about drugs. They took their names from everywhere, which resulted in bands like Ultimate Spinach, The Chocolate Watch Band, and Lothar and the Hand People. In San Francisco, a group of fans calling themselves the Family Dog began to stage free rock concerts starring local bands who then went on to national fame. The Starship, known then as the Jefferson Airplane, launched their career at these shows, as did Steve Miller, Moby Grape (they were named for a popular joke of the time: “What’s purple and weighs ten tons?”), and the Grateful Dead.

England took back some of the psychedelic glory it was losing to the Americans with the Who’s rock opera, “Tommy”, in 1968, and a young guitar wizard named Jimi Hendrix.

Jimi Hendrix, an American playing in England, was to the guitar what “Max Headroom” is to TV. Where others simply strummed, he bashed, then took the guitar, smashed it to the floor and lit it on fire.

Rock ’n’ roll fans had already seen Peter Townshend of the Who wreck his guitar and the stage, but Hendrix took the audience to an entirely different place than did the Who.

But ’60s rock wasn’t all crash and burn. There was another kind of music that solidly captured the ears of the teenage radio audience. “Bubble Gum” music sounded like its name—sweet and sticky. Bands like the 1910 Fruit Gum Company and the Ohio Express rode to fame with hits like “Simon Says” and “Yummy Yummy Yummy (I’ve got Love in My Tummy).” But many of the bands who played this type of music disappeared quickly. Except for The Monkees.

The Monkees were the creation of Don Kirshner, a record company executive who was interested in producing an American competitor to the Beatles. They were an instant success.

Their weekly TV show was watched faithfully by millions of young fans and their records sold amazingly well. After four seasons of acting like rock stars, however, The Monkees disbanded and the four wouldn’t share a stage again for nearly 20 years.

As the ’60s went on, things became more and more serious. The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper in the summer of 1967, an album that stood the music world on its head. While it was claimed to hold secret messages about drugs, it was simply a superb grown-up album for the Fab Four. In the first weeks of Summer 1967, there was nowhere you could go where you wouldn’t hear the album being played.

While the Beatles grew up, so did their fans. They became angry at the war the U.S. was fighting in Vietnam. Protest demonstrations burned on college campuses everywhere and, of course, the music reflected it. In “Street Fightin’ Man,” the Stones claimed the time was right for “violent revolution.” Though the Woodstock Music Festival united a generation for three days in 1968, everyone snapped back to reality when four students were killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State University. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young captured the feeling of the time with “Ohio.”

It was, as the Temptations sang, a “Ball of Confusion.” Thousands of kids left home to find themselves. It was as though they were the “rolling stones” that Bob Dylan sang about.

1969 saw Hell’s Angels kill a man at a Rolling Stones concert in Altamont, the same year that mini-skirts rose ever higher. It was a strange time.

In 1969, the Beatles released their last official LP, Abbey Road. It sparked rumors that Paul McCartney was dead. He was very much alive, but the ’60s weren’t. One year later, the Beatles broke up. The magical ’60s were over.