Wherein The Monkees, finally a group, battled and won the right to play their own music

At Screen Gems they call it No Man’s Land. It is given a wide berth by the Studio’s Sta-Prest pants set. It is a shabby green building, converted from a duplex apartment—its walls scuffed, its steps in a crumbling state of disrepair—crammed between buildings at the far end of the parking lot. On the wall of the cluttered second-floor reception room is a sign which says War Is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Beings, an ancient advertisement for a Lydia Pinkham Calumet Corset Clasp, and a photograph of LBJ bearing the legend, He Who Meddles in a Quarrel is like One Who Takes a Passing Dog by the Ears. Proverbs 26:17.

This is GHQ for The Monkees. The Monkees are the creation, in the image of The Beatles, of two ambitious young men named Bert Schneider, 34, and Robert Rafelson, 33, the former the son of the president of Columbia Pictures, of which Screen Gems is the TV arm. Schneider and Rafelson advertised in the Hollywood trade papers for “four insane boys, 17–21, with the courage to work,” found them, and through the marvelous alchemy of TV converted them into the hottest new act in show business—an accomplishment rendered all the more remarkable by the fact that the boys could not play their instruments well enough to record the hit tunes that made them famous. Someone else did it for them. Act? Well, they didn’t really act either: They “romped,” to use their director’s favorite term.

It wasn’t easy, of course. True creation never is. First off you have to have the whole hippie movement going for you. You must acknowledge that the world is divided into two parts: (1) the turned-on people, the flower children—the seekers and true believers who dig the mind-blown scene; and (2) the up-tight straight world of people over 30 with their square Hawaiian sports shirts, their down-trip attitudes and their Sta-Prest ideas of what the world is all about. You have to have been a student of a movie called “A Hard Day’s Night,” starring The Beatles, which established the ground rules for making this wacky, way-out musical scene back in 1964. Since your four insane boys are generally bereft of anything resembling professionalism, you have to invent a whole “subjective” routine for them, a kind of Freudian free-association thing in which they tell you what it feels like to be a teapot while riding a motorcycle standing up; and you photograph it all with a hand-held camera. You have to figure out a “sound” for them, too, since they either can’t, or you don’t trust them to, figure it out for themselves. You import professionals, placing in charge of the whole musical operation a young Galahad of the record wars named Donny Kirshner, described as “the Dr. Timothy Leary of sound,” strictly a man with a telephone in his Cadillac.

Now you are holding all the aces—you hope—in a four-way game involving huge profits in records, a TV show (which is really a kind of superpromo for the record sales), personal appearances and merchandising. You have galvanized the entire resources of a TV-and-movie-making studio behind you. The studio is making, Kirshner is making, you are making (or stand to make) millions. Your boys—“corporate pawns,” one of your record producers once had the poor taste to call them—are making a quick $500 a week. But that doesn’t really matter when you consider their collective 5 percent of the record take, not to mention their cut of the merchandising (10 percent of Raybert Productions’ share) or the fat pickings (30 percent of the net) they stand to make from the Hawaiian, European and American tours (on their first try they netted $40,000 each from nine play dates)—if they can teach themselves to play their instruments well enough to handle it all.

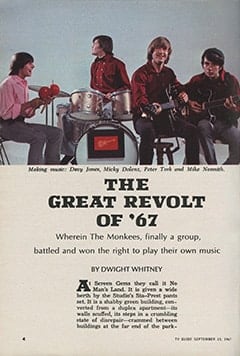

There is just one thing wrong with the picture. The dream is built on a house of cards. The TV Establishment is not ready for The Monkees: worse yet, The Monkees are not ready for the Establishment. Young, frightened, confused, they are entirely unschooled in the nuances of handling a big success. They are thumped, bumped and rattled around like marbles in a tin tub, fearful that someone will discover them for what they are: four not very secure boys named Davy Jones, ex-Newmarket jockey turned stage singer; Micky Dolenz, ex-child star of Circus Boy; Peter Tork (nee Thorkelson), an economics professor’s son, who once played the coffee-house circuit; and Mike Nesmith, onetime protest singer—all of whom sense with increasing, discomfort that they are being manipulated.

Suddenly there are too many people pulling on them, expecting things that they do not know how to deliver. They are expected to “break up the whole damn scene—that’s the way to get publicity!” In their nervousness they begin to compete with each other to see who can say the “funniest” things. Understand you have a wife, Mr. Nesmith?… Uh, yeah, she’s got a hairy chest and is a good basketball player… Once they entertain a lady teen-scene journalist by playing catch with the salad.

Then disaster strikes. The scene is Chasen’s restaurant in late June 1966, before the first Monkees show reaches the public. NBC is entertaining its affiliates, the men who decide what their stations will carry, and stars of the new fall shows are making appearances. While the whole hippie movement has by this time gained wide acceptance in American life, the affiliates are conservative, skeptical men, known to be opposed on principle to anything long-haired.

“Bert Schneider was against the boys’ going,” recalls a behind-the-scenes participant. “He figured it for a square scene and the affiliates wouldn’t dig it anyway. But the network insisted; the affiliates had to be won over. The head writers had a sketch for them, and the boys were supposed to kind of come in on the end of things, make a quick appearance and get out.

“But things ran late. They stood outside, tired, nervous, unfed. I said, ‘Are you guys going to do the material?’ ‘Hell, no,’ they said. Somebody had dragged along a stuffed peacock. They played volleyball with it, stopping traffic on Beverly Boulevard. Micky got into the restaurant’s switch box and turned off all the lights. Finally they were introduced by Dick Clark. Since they hadn’t any musical instruments—we were afraid to let ’em try to play—they did ‘comedy’ material. Micky shaved with the microphone. Davy pretended he was a duck. The jokes began to die. The affiliates were already hostile and what was not needed was a bunch of smart-aleck kids.

“On the way out I heard an affiliate say, ‘That’s The Monkees? Forget it.’”

The network was later to pay dearly for this unseemly display. At least five key stations failed to pick up the show, resulting in national ratings which did not accurately reflect its true popularity. In the studio it caused a widening of the rift between pro- and anti-Monkee factions.

The Chasen’s fiasco did another thing, too. It suddenly attracted the attention of the big-time press. Schneider, who believed he could “control” the press, held the news hounds at bay as long as he could. But by midsummer he was in the soup. He had four boys but no music. Kirshner, the president of Colgems—a new subsidiary of Screen Gems’ music division especially created for the Monkee music and in which, significantly, RCA Victor had an interest—arrived in town and quickly decided that he must use professional musicians to “create” The Monkees sound. He came up with “Last Train to Clarksville,” by Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart.

“I heard them. They were loud,” Kirshner recalls, of his first exposure to The Monkees. “It was not the right sound. Not a young, happy, driving, pulsating sound of today. I wanted a musical sex image. Something you’d recognize next time you heard it. Davy was OK—for musical comedy. Mike was the weakest singer as far as I was concerned. Micky was a natural mimic. And he had the best voice for our purposes. He did the lead on ‘Last Train.’ Davy and Peter sang some background harmony. Mike wasn’t on the record at all. Boyce and Hart and hand-picked professional musicians played it. The boys told me, ‘Donny, anything you want to do is OK with us.’

“Later we tried Mike on the lead of ‘I’m a Believer.’ We had to take him off.” It was the beginning of their disenchantment.

By September, Kirshner’s “Last Train” was on its way to the top of the record charts, where it would remain for an embarrassingly long time. But, thanks in part to the Chasen’s affair, Schneider’s newly minted TV show was residing in the bottom half of the Nielsen charts.

Indeed the situation was trying for Schneider. His autocratic attitude (“People over 30 are square!”) infuriated the rest of the studio. Reporters were treated like Russian spies. Consequently he had the press on his neck; the New York Times was about to leak the first story hinting at the boys’ musical ineptitude. And he was facing the constant threat that his boys, increasingly aware of their power, might explode at any time.

Kirshner, by his apparent unwillingness to treat them as anything but overgrown children, was not helping this along any. To make matters worse, Kirshner had 15 percent of Colgems’ net profits before taxes. Since some 6,000,000 singles and 8,000,000 albums had been sold by midseason, Donny was growing rich. The boys had to struggle along on a 1.25 percent royalty apiece, a fair piece of change, but minuscule next to the $300,000 Kirshner had already made and the upwards of $5,000,000, he stood to make from the Monkees operation over a five-year period.

The Monkees were, moreover, artistically hung up: “The music on our records has nothing to do with us,” the spokesman for the group, intense young Mike Nesmith, had said once and was ready to say again. “It’s totally dishonest. We don’t record our own music. Tell the world we’re synthetic because, dammit, we are! We want to play our own.”

It was not so much an ultimatum as an agonized cry. Because what they really craved was that good old-fashioned “straight” attribute—acceptance. They just didn’t know how to go about getting it. Their pride was hurt. They were increasingly aware that it was The Beatles, The Byrds, The Mamas and the Papas to whom the musical world looked with genuine if sometimes grudging admiration. At the Monterey International Pop Festival it was those darlings of the Haight-Ashbury crowd, The Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead, who mind-blew the hip crowd. The Monkees felt like clowns.

In the beginning they accepted this limitation dutifully. Before the show started shooting in June 1966, they were being trained as “improvisational” actors and taking a crash course in the musical fundamentals. What made the music situation doubly impossible was that they were acting 10 to 12 hours a day. Since no music recording is ever done on a set—the actors “lip-sync” the words to a playback—there simply was not time for amateur experimentation.

Thus the boys were frustrated by the very system that enriched them. Still, they had to become proficient enough to get by on the concert stage, where no musical stand-ins were possible.

They practiced feverishly, put a saddle on their jumping nerves and, with the help of a planeload of equipment and some psychedelic stage effects whomped up for them by choreographer David Winters, opened in Honolulu on Dec. 3. “They were a smash,” reports one eyewitness. “The music? With all those screaming kids, who can tell?”

Meantime, the love-match between the boys and Kirshner (“To the man who made it all possible,” read the inscription on the 48x48 photograph they had given him in the fall) was starting to decline. It began with Mike Nesmith. Mike fancied himself not only a musician, but a record producer and composer as well. Kirshner, a rough-and-tumble musical pragmatist to the lapels of his Sy Devore suit, rode a narrow line between tolerating and patronizing them. He listened—but not very hard to the tapes they recorded on their own in the naive hope that one of them would please “Donny.” He made vague promises that (the boys later claimed) he never kept. The father-figure image, once exclusively Kirshner’s province, was shifting back onto producer Schneider, a self-styled overage (34) up-tripper who was more adept at telling the boys what they wanted to hear.

Clearly a showdown was coming. And come it did. Surprisingly, it also produced an emotion-packed confrontation between Kirshner and the boys, who were tired of being “corporate pawns,” stung by the taunts of their musician friends and scorned in the press as being the rock ’n’ roll group that didn’t rock and didn’t roll.

In late January 1967 The Monkees met with Kirshner in his $150-a-day bungalow suite in that swank bastion of Hollywood squaredom, the Beverly Hills Hotel. They had come to plead their case with their once-adored mentor. Kirshner was on the spot. RCA Victor, which distributes Colgems records, was pressuring him for a third single and album. He needed the boys and yet—well, uh, he didn’t need them. He was flanked by his henchmen from the studio music division, Lester Sill and Herb Moelis; and, to make it even more grotesque, had four Gold Records, those coveted totems of million-copy record sales, ready to present to the boys. The Monkees were alone; Schneider wisely had stayed home.

Gingerly they came on with their demands: that they play their own instruments, choose their own songs; Kirshner would oversee. Mike later described Kirshner’s reaction as “a little uneasiness, the sweaty-palms-in-the-eye syndrome.” Kirshner replied that he had prepared four demos (test records) of possible tunes for them to record; he added a short, blunt recapitulation of the facts of life of the music business. Mike flushed and turned on Kirshner.

“Donny,” he said, “we could sing ‘Happy Birthday’ with a beat and it would sell a million records. [Your argument] is no longer valid because we are The Monkees and we have that incredible TV exposure.”

When Kirshner, unnerved, backed off, Mike threatened to quit. Herb Moelis said, “You’d better read your contract.” Mike whitened with rage. He disliked Moelis (“Why? Why do I dislike strawberry ice cream? He didn’t respect me as an artist!”). Then he smashed his fist through the wall of Kirshner’s $150-a-day bungalow. Kirshner caught up with Mike in the lobby and thrust the Gold Record upon him. Lester Sill drove Mike, clutching the Gold Record and smoldering, home.

Later Mike told his “angel of peace,” the ever-conciliatory Schneider, “I blew it. I shouldn’t’ve lost my temper. But it’s horrible to be No. 1 group in the country and not be allowed to play your own records.” Schneider said, “Well, it’s rewarding to see you guys act as a group rather than four egotists who don’t pull together.”

To which Mike replied, “It’s the first time we’ve had one wagon to pull.”

From then on the situation deteriorated rapidly, with the other boys falling in line behind Mike. “Bert knew I meant it when I said I’d quit the whole complex, pack up my gear, go to Mexico or Tahiti, eat coconuts and let everybody sue me.” Amazingly, Schneider believed him, the studio believed him. The ever-realistic Kirshner obviously didn’t. It was just too incredible. But less than a month later Kirshner was out, flower-power was in, and Screen Gems and Columbia Pictures had law-suits totalling $35,500,000 on their hands—what Donny Kirshner figured the rude abrogation of his contract was worth.

The boys took off on a much-needed vacation, returning a few weeks later to, of all places, a sound-recording stage. The new album, “Headquarters,” is, for better or worse, all theirs. Mike said, “It makes the group tighter and closer and proud as punch…” And zap! Happy Birthday! There it was, right at the top of the charts, just one notch below The Beatles! The up-tight world of straights with their Sta-Prest pants defeated at last! It was a good, heady, up-trip feeling. And Nesmith was pleased to recall that transcendental moment when, listening to the car radio later in the spring, he first heard the real, genuine bona-fide Monkees doing their thing on “The Girl I Knew Somewhere.” Groovy! Super-zappy! Mind-blowing! Cosmic! Mike honked the horn impatiently for his wife and his friend and his brother-in-law to come out. “Hey,” he yelled, “want to sit in on a moment in history?”